Devopsdays Amsterdam 2019: day one

Table of Contents

This is the seventh time devopsdays is organized in Amsterdam. The event was sold out twee weeks in advance and has the highest attendance rate thus far. I was fortunate enough to attend again this year.

Observability for emerging infra: what got you here won’t get you there — Charity Majors

[Slides]

Charity has been a systems engineer since was 17 and she’s done her fair share of being on call. As a result her approach to software contains stuff like:

- The only good diff is a red diff.

- Junior engineers ship features, senior engineers kill features.

She co-founded Honeycomb.io a few years ago. Her company wants to help understanding and debugging complex systems.

Vendors often talk about the “three pillars of observability”, meaning metrics,

logs (which is where data goes to die

) and tracing. Which

happen to be the categories of products they are trying to sell you.

The architecture that is being used today is much more complex than the humble LAMP stack we used years ago. Because of this increased complexity you go from “known unknowns” to “unknown unknowns.” Testing is also harder since you cannot simply “spin up a copy” if you want to test something. As a result, monitoring isn’t enough—you need observability since you cannot predict what you need to monitor. Plus: you should fix each problem. So every page should be something new; it should be an engineering problem, not a support problem.

Due to the infinitely long list of almost-impossible failures,

your staging environment becomes pretty useless. Even if you capture all

traffic from production and replay it in your staging environment, the problem

you saw in production does not happen.

Good engineers test in production. Bad engineers also do this, but are just not aware of it. You cannot prevent failure. You can provide guardrails though.

Operational literacy is not a nice-to-have

You’ll need observability before you can think about chaos engineering. Otherwise you only have chaos. If it takes more than a few moments to figure out where a spike in a graph is coming from, you are not yet ready for chaos engineering.

Monitoring is dealing with the known unknowns. Great for the things you already know about. This means it is good for 80% of the old systems, but only 10% of the current systems.

Your system is never entirely “up”

The game is not to make something where nothing breaks. The game is to make something where as many things as possible can break without people noticing it. As long as you are within your SLOs, you don’t have to be in firefighting mode.

Not every system has to be working. As long as the users get the experience they expect, they are happy.

Engineers should know how to debug in production.

Everyone should know what they are doing. If an engineer has a bad feeling about deploying something, investigate that. We should trust the intuition of our engineers. However, the longer you run in staging, the longer you are training your intuition on wrong data. You should be knee-deep in production. That is a way better way to spend your time. Watch your system with real data, real users, etc.

Don’t accept a pull request if you don’t know how you would know if it breaks. And when you deploy something, watch it in production. See what happens and how it behaves. Not just when it breaks, but also when it’s working as intended. This catches 80% of the errors even before your users see them.

Dashboard are answers. You should not flip through them to find the one matching the current scenario. It’s the wrong way of thinking about problems. Instead you need an interactive system to be able to debug your system. Invest time in observability, not monitoring.

By putting software engineers (SWEs) on call, you can make the system better. The SWEs are the ones that can fix things so they don’t have to be woken up in the middle of the night again. If you do it right, and have systems that behave themselves, being on call doesn’t have to interfere with your life or sleep. This does require organizations to allow time to fix things and make things better instead of only adding new stuff.

Teams are usually willing to take responsibility, but there is an “observability gap.” Giving the SWEs the ops tools with things like uptime percentage and free memory is not enough. Most SWEs cannot interpret the dashboards to answer the questions they have. In other words, they don’t have the right tools to investigate the problems they encounter. You need to give them the right tooling to become fluent in production and to debug issues in their own systems.

High cardinality is no longer a nice-to-have. Those high cardinality things (e.g. request ID) are the things that are most identifying. You’ll want this kind of data when you are investigating a problem.

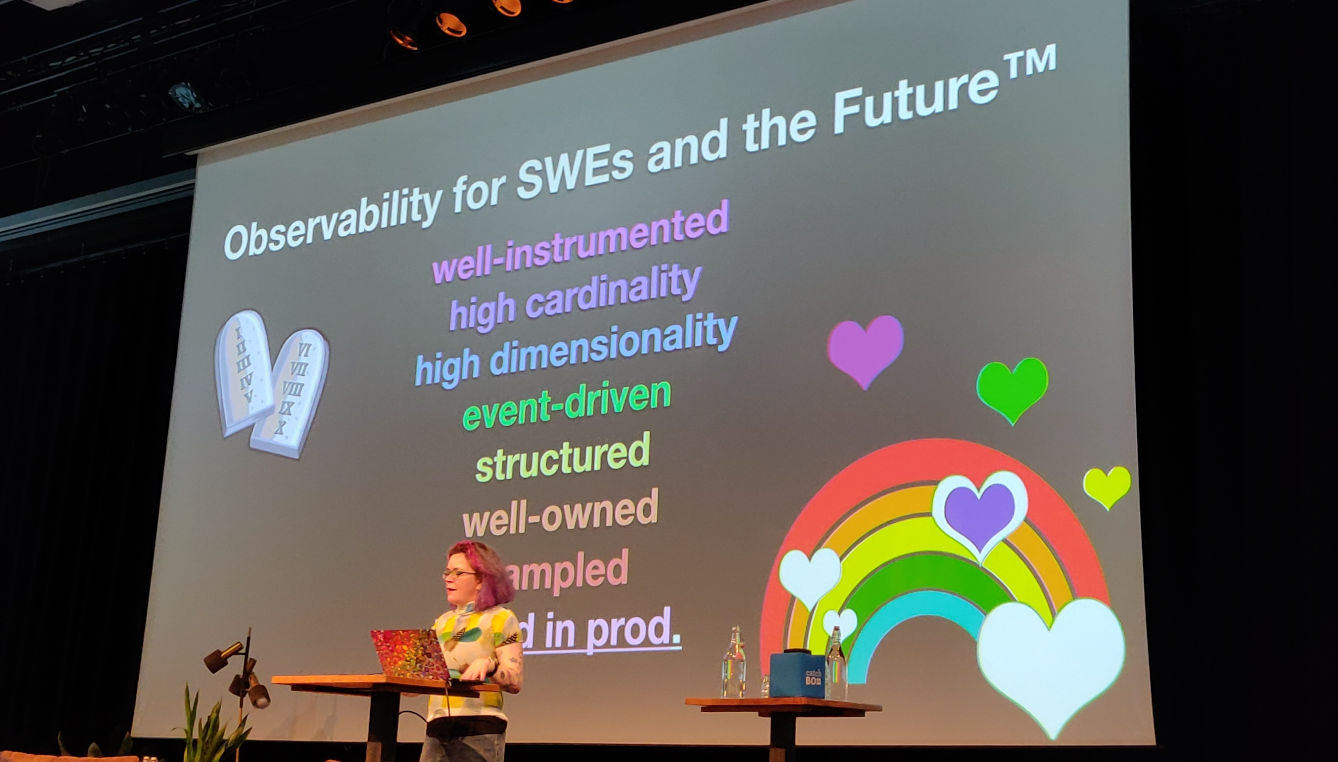

The characteristics of tooling that will get you where you need to go:

- Well instrumented

- High cardinality

- High dimensionality

- Event-driven

- Structured

- Well-owned

- Sampled

- Tested in production

By having this you get drastically less pager alerts.

Great talk by Beau Lyddon: What is Happening: Attempting to Understand Our Systems

You can use logs to implement observability as long as they are structured and have a lot of context (request IDs, shopping cart IDs, language runtime specifics, etc).

Senior software engineers should have proven to be able to own their code in production. They should notice and surface things that are not noticeable. Praise people for what they are doing good and make sure that those are also the things people get promoted for.

How Convenience Is Killing Open Standards — Bernd Erk

Thanks to the POSIX standards, Solaris admins could still do things on HP-UX systems. Then the GNU toolset came along. And Linux. Communities. Diversity.

As an industry we have a talent to forget everything we learned before. We jump from one new thing to another, but we keep making the same mistakes over and over.

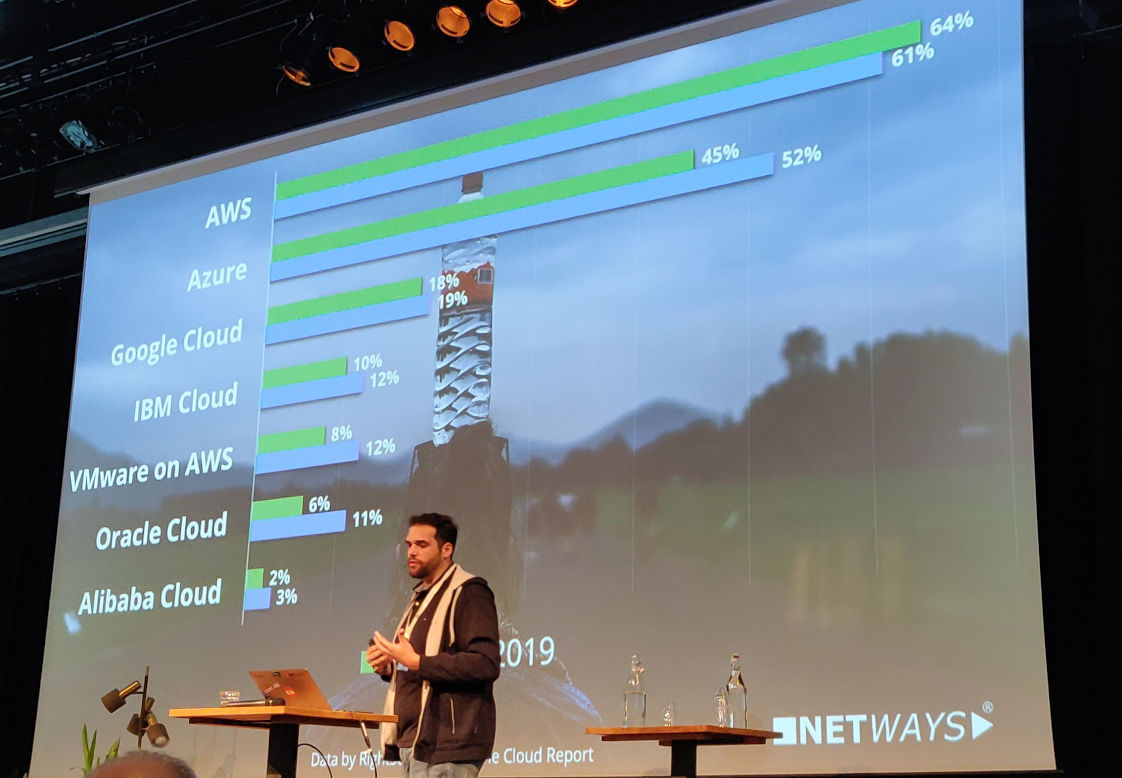

We have more open source software than ever before. But we also have a dramatic change in the infrastructure. Public cloud becomes more popular. But is this a problem? Isn’t this just evolution?

Open source does not mean open standards however. An API is also not a standard, even if it is open. Standards are defined by organizations like IETF and W3C.

We have an unbalanced market. AWS and Azure are much bigger than the others. They all have their own APIs, but there is no open standard! This is why Terraform is so popular: it solved the missing standard problem for you. But you still need to be aware that an EC2 instance is different from an Azure machine though.

Open source has an impact on open standards.

Amazon is offering services that are based on open source software (e.g. Amazon Elasticsearch Service and Amazon ElastiCache). As a result customers don’t talk to Elastic, but to Amazon. Google does this better and (at least for some products) forwards issues to the developers.

Some companies that create open source software have now come up with new licenses to prevent e.g. Amazon offering their product as a service. This creates uncertainty for companies that want to use the technology.

Open source and open standards need support (money). As an industry we need to make sure that they have chance to have a place in the market.

Customers should ask their vendors to contribute back to the creators of the software.

For a lot of companies infrastructure is overhead. Using cloud services poses a risk, but a risk you perhaps can accept given the convenience those cloud services bring along. Lock-in is a risk, as is slowness.

Bernd himself would also use the cloud for a startup to get off the ground quickly. After one to two years you’ll probably have to redo your setup. Perhaps this is a good time to think about how to move forward? What do you want to be flexible about?

Economics in an unbalanced marked are not good. See the pharmaceutical market where there are a few big players and prices of medicines sometimes explode. Being able to work with different providers and be interoperable is important. We need variety.

Unfortunately the cloud providers don’t have an incentive to work towards open standards and to make it easier for customers to hop around from one provider to another.

Diversity is up to us. Not just on the work floor, but also in the technology we use.

Come listen to me, I’m a fraud! — Joep Piscaer

This talk about impostor syndrome. 70% of people experience it.

Joep’s “definition” of it:

Your internal measuring stick is broken.

Everybody is unsure, but nobody talks about it. In IT this problem becomes worse. We talk about “best practices,” but there are so many ways to do things, how do you know what is the “right” way? Perhaps the way you are doing things is perfectly fine.

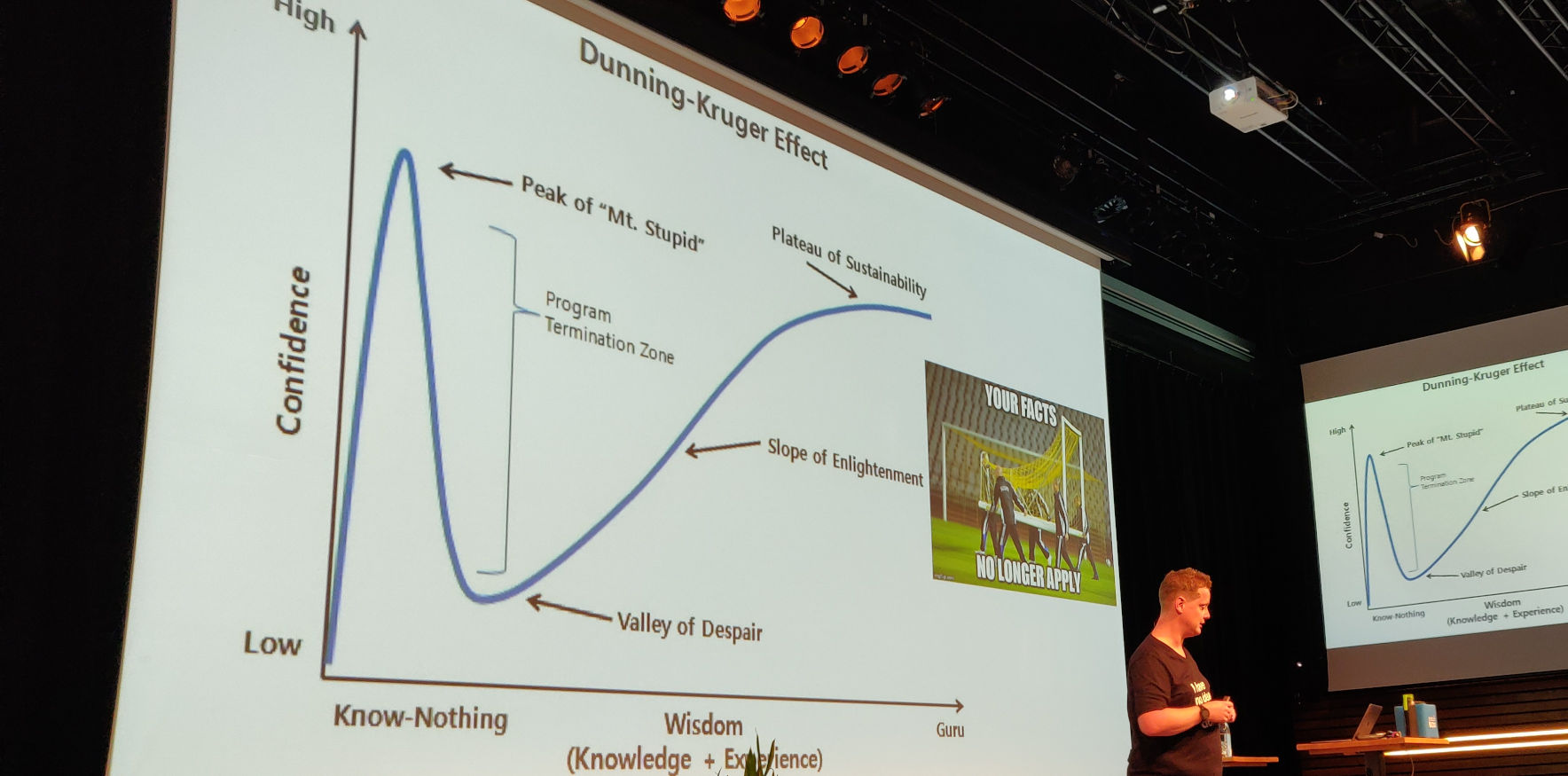

Joep talked about the Dunning-Kruger effect. But in IT the technology landscape changes in a fast pace. The goalpost is moving constantly.

What can you do about it? How do you recalibrate your internal measuring stick?

- Say positive things about yourself in front of a mirror to diminish the negative thoughts about yourself and strengthen the positive ones.

- Don’t compare yourself to other people, especially people on the internet.

- Learn how to receive compliments.

- Write down compliments and accomplishments and look at the list regularly. This also learns you about the perspective of others.

- Brag about one or two occasionally.

- Learn from others and teach others about your thinking process (pair programming, pair review (instead of peer review), speak publicly, etc).

- Trust others, you are not alone. Talk to others, participate in conversations. Show yourself.

- Get hobbies. A hobby is something you like to do and where you can fuck up without consequences.

To discover why you have impostor syndrome, you have to identify your limiting beliefs.

A number of TED talks you should see:

- The power of vulnerability, by Brené Brown (Tip: watch this in a comfortable setting with your partner nearby to support you if needed.)

- Inside the mind of a master procrastinator by Tim Urban

- Imposter Syndrome by Mike Cannon-Brookes

Using Design Methods to Establish Healthy DevOps Practices — Aras Bilgen

Companies that want to do DevOps are usually enthusiastic about tools and processes. Culture is a harder subject… Even if you show data that demonstrates the importance of the cultural aspect of DevOps, there’s not much understanding.

Most people think about design as making things beautiful. But it also makes things work better. It makes things more visible and matches the conceptual design with the mental model.

Design can reframe problems.

Uber is not just about getting a ride, but it is rethinking the way getting from A to B works. Airbnb is not only about getting a nice room, but it is rethinking the hospitality industry overall. Starbucks sells coffee, but also turns community spaces into places where you can hang out and have conversations over coffee.

Good designers:

- Work with actual end users (not managers or product owners)

- Welcome ambiguity

- Give form to ideas

- Co-create in a safe setting

- Experiment and revise

Instead of talking to customers about their tools, processes and culture, you could start with interviews and having collaborative process maps workshops where you look at the entire flow from idea to when it explodes in production.

Don’t just offer the out-of-context “best practices” from the DORA State of DevOps report, but have challenge mapping workshops. This leads to solutions that are applicable and often don’t even need to be imposed but are willingly implemented.

Do diary studies: what do people actually do and what makes working hard for them?

Two takeaways:

- Mindset matters more than background. You don’t have to be a designer to do this.

- Stop and listen with an open heart and no agenda.

Serverless is more FinDev than DevOps — Yan Cui

(This was a fast-paced talk and I did not have time to make many notes.)

Serverless means that:

- you only pay for what you actually use

- you don’t need to worry about scaling

- you don’t need to provision and manage servers

Function-as-a-service: upload code to the cloud which gets run when called and your function then handles the events.

Serverless is interesting because:

- scalable

- pricing (can be cheaper, but not always!)

- resilience

- security

- greater velocity from idea to product

- less ops responsibility (no servers to manage)

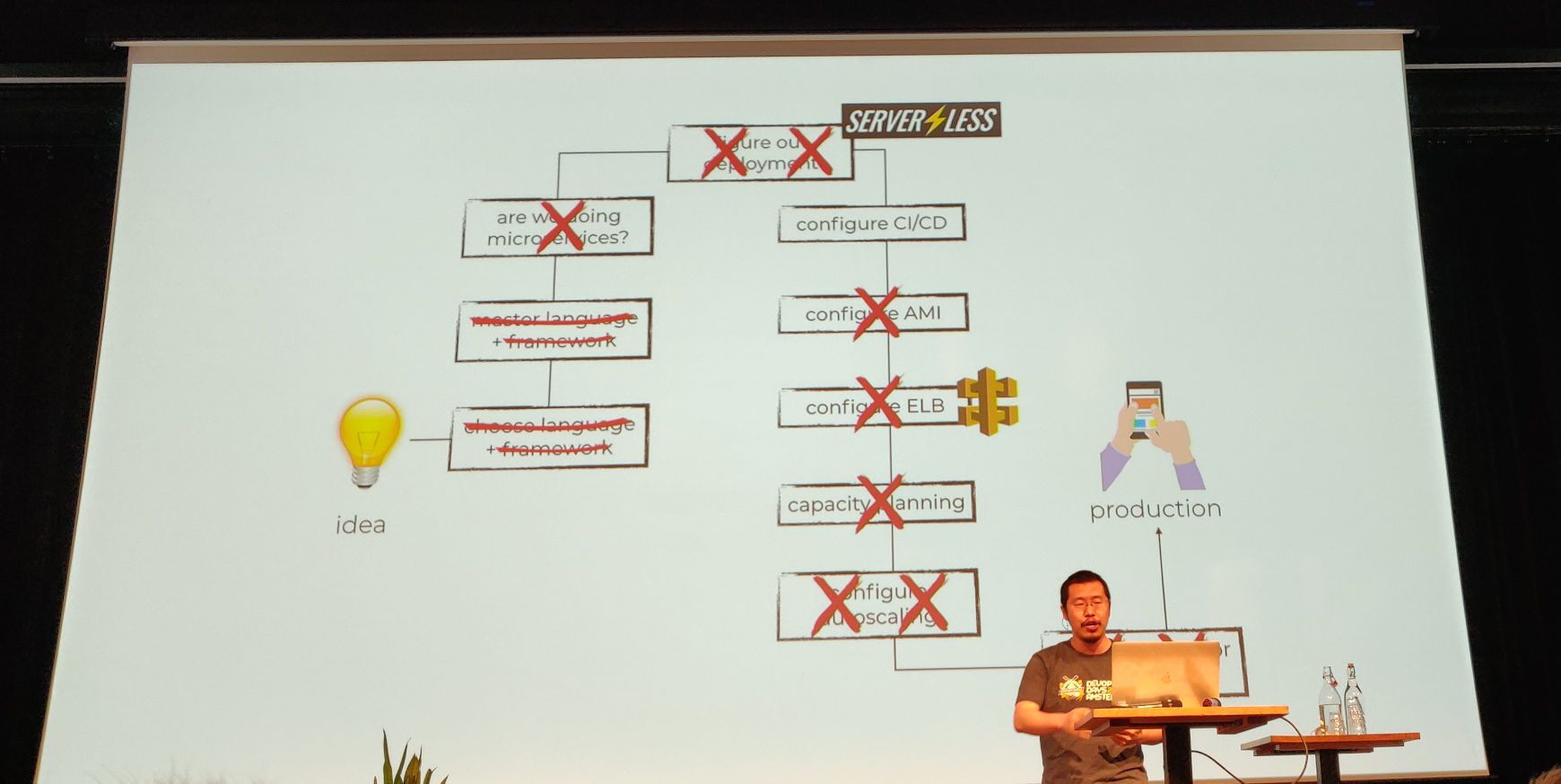

With regards to the velocity: with serverless you can remove a bunch of steps from your process, like figuring out deployment, configuring an AMI, ELB or autoscaling.

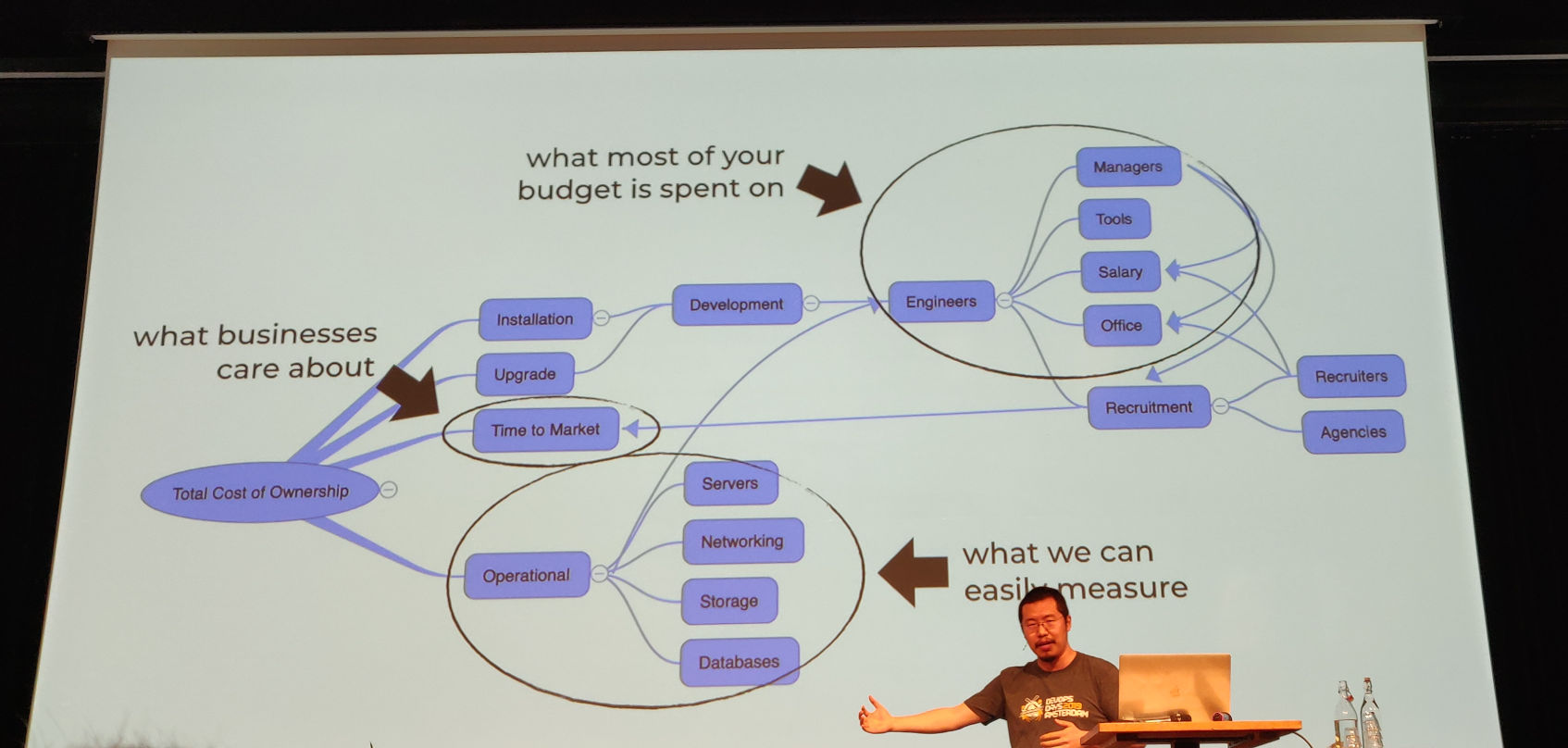

Return on investment

Companies are looking for a return on their investment.

We tend optimize what we can easily measure: operational stuff. But most of the budget is going to engineers, managers, tools, etc.

Serverless might cost just as much as e.g. running EC2 instance and perhaps it costs even more, but you can get so much more done.

With a server you have the same costs no matter if you have only a single transaction or 100. This means that the transaction costs (costs divided by the number of transactions) is variable. To make matters worse: there are often multiple services running on a since server. This makes it even harder to estimate the transaction cost or the cost of a feature.

The pay-per-use characteristic of serverless is useful in this contest. It makes it much more clear what the cost per transaction is.

Ignites

Ignites are short talks. Each speaker provides twenty slides which automatically advance every fifteen seconds.

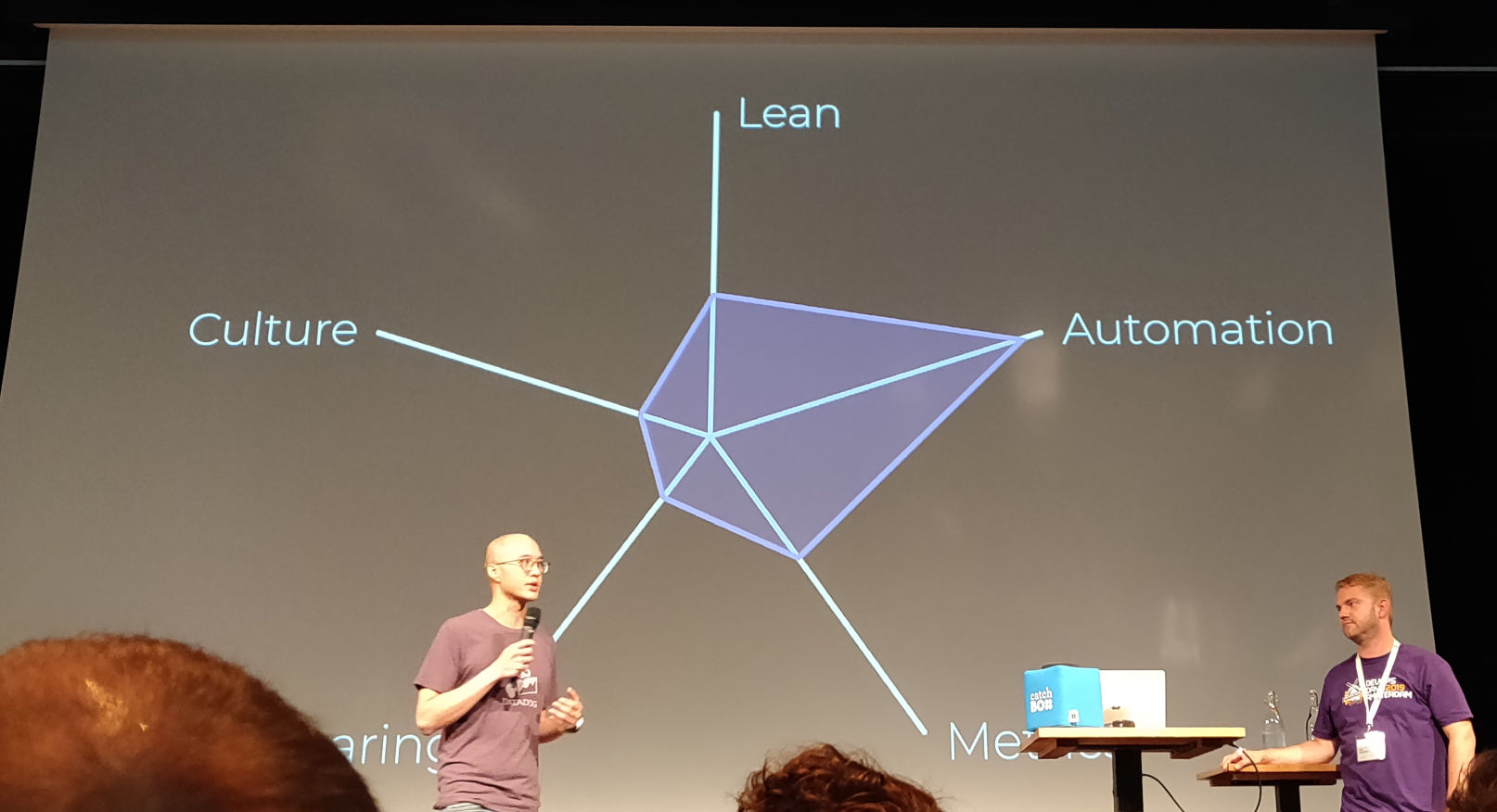

The IJ & the shape of DevOps — Jason Yee

The shape of the IJ has changed though the years. Has the shape of DevOps changed over the years?

Well, now there is CLAMS (or CALMS), which stands for:

- Culture

- Lean

- Automation

- Metrics

- Sharing

If you would plot each of these on an axis, you can plot an organization on it.

Now imagine the circumference is an elastic band: if you pull it on one axis, you’ll decrease the value on the other axes.

Work around the circle. If DevOps means automation for you, this helps being lean, which shapes your culture, which helps sharing, etc.

Evaluate your organization: what is it good at, what are you working on? It’s a natural process, a dynamic movement. Work on all axes.

What you see is what you get for AWS infrastructure — Anton Babenko

Cloud architects and DevOps engineers want to have a faster conversion from idea to working project.

With Cloudcraft you can visualize your AWS infrastructure. With modules.tf you can export that diagram to Terraform code. And with Terraform you can manage your infrastructure. And we have come full circle.

YAML Considered Harmful — Philipp Krenn

Why do we use YAML in the first place? We want to have a human readable format (so XML is out), and we want to be able to place comments in our code (which means JSON is out of the picture).

There are a few issues with YAML though. To name a few:

Suppose you have a port mapping in

your docker-compose.yml:

ports:

- 80:80

- 22:22

Looks fine? Except it is not fine, because YAML will parse numbers separated by a colon as base 60 (sexagesimal) numbers if the numbers are smaller than 60. So the second line is not parsed as the string “22:22” but as the integer 80520, which is something Docker (understandably) cannot handle.

Another example is this:

countries:

- DK

- NO

- SE

- FI

However, “NO” is a falsy value, so the countries list will contain three

strings and a boolean.

If you want a DSL, please use a DSL, not YAML.

Alternatives:

- Maybe jsonnet?

- XML: problematic for humans, it’s meant to be parsed by computers computers

- JSON: doesn’t feel right

- INI: no hierarchy, parsers on different platforms behave differently

- TOML: indentation is optional

- JSONx: worst of all worlds

When you want to write YAML:

- indent properly

- quote just about everything